In response to rising tensions over Greenland, thousands of Danish consumers have turned to mobile applications aimed at identifying and avoiding American products. This shift in consumer behavior follows comments from former President Donald Trump regarding Greenland, leading to a spike in downloads for two specific apps in late January.

The first app, Made O”Meter, developed by 53-year-old Ian Rosenfeldt from Copenhagen, experienced a remarkable surge, gaining approximately 30,000 new users within just three days when tensions peaked. Since its launch in March, the app has amassed over 100,000 downloads.

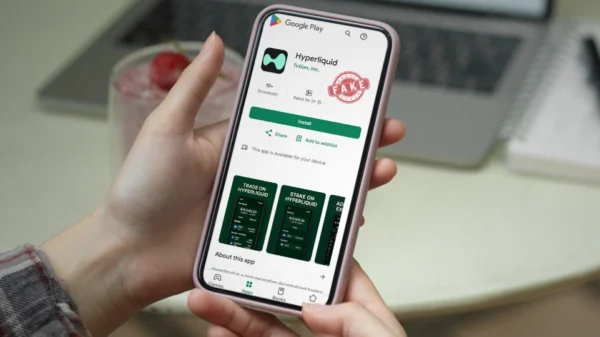

The second app, NonUSA, also gained significant traction, surpassing the 100,000 download milestone by early February. On January 21 alone, its 21-year-old creator, Jonas Pipper, reported that 25,000 users downloaded the app, with some users scanning as many as 526 products in a single minute.

These apps offer a practical solution to a growing frustration among consumers. Traditional barcodes do not indicate whether a product is American or European, prompting Rosenfeldt to utilize artificial intelligence to help users find European alternatives. The app allows users to customize their preferences, such as blocking all U.S.-owned brands or opting to only purchase from EU companies, with a claimed accuracy of over 95%.

Initially, Made O”Meter recorded around 500 daily scans last summer, but this figure skyrocketed to nearly 40,000 on January 23. Although the daily scans have since decreased to approximately 5,000, the app has retained over 20,000 regular users in Denmark, along with additional users from countries including Germany, Spain, Italy, and Venezuela.

As reported by various outlets, Trump retracted some of his aggressive tariff threats following discussions with NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte. The EU also held emergency meetings, with European leaders warning that tariffs could harm transatlantic relations. Although details about Trump”s framework deal concerning Greenland”s minerals and Arctic security remain sparse, U.S. and Danish officials initiated technical discussions in late January.

Despite the significant download numbers and consumer engagement, experts like Louise Aggerstrøm Hansen, an economist at Danske Bank, noted that U.S. food imports comprise only about 1% of Danish food consumption. Rosenfeldt acknowledges that his app is unlikely to impact the American economy directly. Rather, he aims to send a message to grocery stores about the importance of supporting European producers.

Pipper described his app as “a weapon in the trade war for consumers,” highlighting that about 46,000 users are based in Denmark and an additional 10,000 in Germany. Many users express feeling empowered by using the app, indicating a collective desire to regain control in the current geopolitical climate.

The ripple effect of this movement extends beyond Denmark, with NonUSA finding users in other Nordic countries such as Norway, Sweden, and Iceland. The interconnectedness of these nations means that threats perceived by one can resonate across the region.

While consumer choices alone may not significantly affect the broader economic landscape, there is potential for greater influence if institutional investors or major retail chains begin to align their strategies with these sentiments. For instance, AkademikerPension, a Danish pension fund, divested $100 million in U.S. Treasury bonds in January in response to the Greenland situation, a move dismissed by U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent as inconsequential.

Ultimately, this situation highlights deeper issues regarding public sentiment and national identity. Danish citizens continue to express goodwill towards the American populace while voicing discontent over their government”s actions. As Rosenfeldt articulated, “Danish citizens love the American people, but we don”t like the way that the government is treating Europe and Denmark.”